Dec 2021

(Essays on this site are from my time at NYU. The prompt for this essay was something along the lines of “write an introductory essay on a major artist’s career.” I attempted to conduct an AP Seminar project revolving around his philosophies in high school which was a miserable failure, so I took this opportunity to do what I wanted to do in the first place, which was just talk about the work.)

It’s too late a night in suburban Los Angeles where fragile housewife Mabel Longhetti emerges from the bathroom having slit open her hand in what appears to be an attempted suicide. “I was just tired,” she eventually explains. The brittle mother trips over her own feet while keeping her kids rounded up in her arms, trying not to stain them with her own blood. An exasperated, lazy-eyed husband finds his confused children at the knees of his manic wife in the midst of another one of her episodes.

Nick Longhetti takes a long, sad breath on the stairs. After separating his wife from the kids, he shouts the last thing he’d ever want to do, revealing the true hopelessness of his character by failing to control his most backwards, intrusive thought.

“I’LL KILL YOU!! I’LL KILL THOSE SONS OF BITCHIN KIDS!,” he professes.

As the worried children run back to their drowsy mother, now laying on the carpet, he can’t help but tearfully smile at them. They’re just worried about their mother! By the end of A Woman Under the Influence’s (1974) thirteen-minute finale, Mabel has put the kids to bed, Nick tended to his wife’s wound, and the two have willingly fixed their home back together. The feature, one of seven major collaborations with wife Gena Rowlands, is known as Greek-American director John Nicholas Cassavetes’ greatest cinematic achievement.

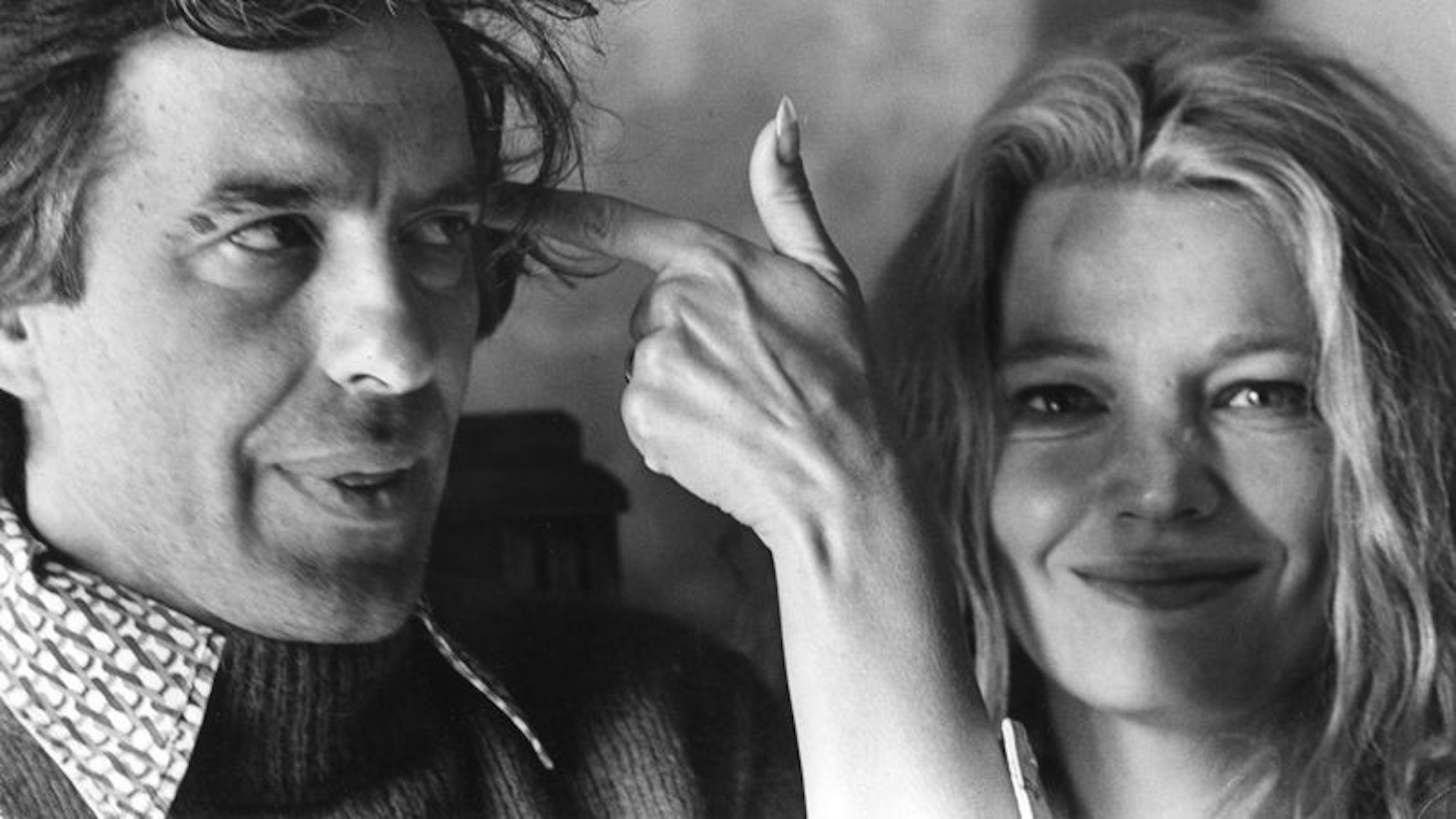

The two met while studying at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, and while John would spend several months trying to convince his future muse out on a date, they’d eventually be known as American independent cinema’s “it couple.” Like many stars of the time, their decades-spanning careers began as actors on small off-broadway productions, eventually leading to starring television roles by the mid-1950s. Around this time, Cassavetes’ growing disillusionment with the dramatic content of American film studios redirected his primary interests to independently producing his own films.

With the success of Cassavetes’ directorial debut Shadows (1959), often pointed at by film historians as the blueprint for all independent cinema, the duo eventually migrated from New York City to Los Angeles. There, John’s two-picture deal with Paramount would mark the beginning of a financially burdened career for the Cassavetes-Rowlands family, rich in nonconforming film philosophies and lacking in any major studio assistance. Despite copious amounts of posthumous success (ranging from DVD releases by arthouse label The Criterion Collection, as well as retrospective screenings across avant garde Manhattan and L.A. cinema houses beginning in the 1990s lasting into today), the violently “allergic-to-sentimentalism” energy behind his films was never enough to fiscally support his career or convince studios his films were worth major exposure.

Cassavetes would spend his entire life insisting on a personal satisfaction with the content of his films while feeling completely misunderstood by audiences of his time. Distributors felt his approach was both too amateur and complicated for general audiences, yet Cassavetes believed everyone deserved a chance at seeing films the way he knew they could exist: both emotionally affecting and realistic, yet barren of the manipulative tactics often overused in the Hollywood films he’d star in to make a living. The unsolved dilemma of his life stayed consistent throughout his career: how could seemingly never-ending professional failure sustain his motivation to continue practicing his radical method with the intent of achieving both intrapersonal satisfaction and a financially stable life?

Shot nine years after his debut feature, Faces (1968) was a detour from John Cassavetes’s preceding studio-made features Too Late Blues (1961) and A Child is Waiting (1963). After infamously provoking a physical altercation with producer Stanley Kramer over final cut of the latter film, Cassavetes was basically shunned from producing films in Hollywood. I consider Faces (1968) to be Cassavetes’ first sophisticated film of his trademark form, exploring boundless possibilities within a film’s edit by severely askewing from the dry mold provided (and expected from audiences) by the pacing of the average Hollywood feature. The film marked his return to cinema-verite aesthetics, an improvised approach to filming documentary subjects that made its way into the New American Cinema movement of the 1960s with the release of Shadows.

Faces depicts a marriage in the concluding nights of its fragmented, most hopeless phase. The film follows a loose plot over the course of one night where husband John Marley (actor) spends the night with business tycoons and a prostitute (played Rowlands), while wife Lynn Carlin (actor) enjoys the night out with her fellow married female friends and picking up a young playboy (played by frequent collaborater Seymour Cassel) along the way. I remember watching the film with my mother just before quarantine began and the both of us fell straight down the film’s chronologically irrelevant but emotionally resonant plot. After spending two demanding hours between the two unfaithful leads, the characters vocally come to terms with the impossibility of their relationship and share a cigarette in the film’s final scene. The dramatic content of Faces provides an authentically deep understanding of the unavoidable differences between partners in life and the paralleled sense of self-awareness that comes with knowing when it’s just not working anymore. Though both characters cheat on each other, no one character is ever vilified more than the other, if at all. The screenplay’s humanistic portrayal of the deceitful partners further complicates the once blank canvases these characters initially were, one of the many foundational factors to all of Cassavetes’ subsequent works.

Pauline Kael, infamously a harsh critic of Cassavetes’ apparently aimless and contrived work, expels her greatest distaste for his work in her review of his first feature after Faces, Husbands (1970). In the piece, entitled “Megalomaniacs,” Kael doesn’t hesitate at berating not only the film and its maker, but everyone who worked on it and audience members who enjoyed it. She points out that if she were to cut the film more than the studio already had, she’d have cut the film from 2 hours and 16 minutes to only 20 minutes of scenes rid of the film’s leads (Cassavetes himself alongside frequent collaborators Ben Gazzara and Peter Falk).

Kael writes, “One assumes [the characters] are meant to be searching for themselves, their lost freedom, and their lost potentialities⸺and one can guess Cassavetes believes their boyishness is creative. But the boyishness he shows us isn’t remotely creative; it’s just infantile and offensive”¹. She comes off as consistently annoyed by who the characters simply are, as if she’d hate those men who never grew out of being boys if they existed in real life. This critical perception of a slate of overbearingly immature or hypocritical characters became a staple in Cassavetes’ works over the years. Yet as shown by Kael’s disparaging remarks on the Columbia-distributed picture, Cassavetes’ decision to point his camera at the more realistic idea of an aggravatingly witless set of characters grounded in reality went over the heads of critics and audiences throughout his entire career.

Between the commercial failures that were Husbands and his next feature Minnie and Moskowitz (1971), Cassavetes nearly found himself burnt out from low audience numbers. He would eventually be offered residency as a professor at the newly formed American Film Institute, partly due to the success of Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and The Dirty Dozen (1967), both films Cassavetes acted in. John would only accept upon the agreement that he could use the school’s equipment and editing facilities for his next project.

Shot on 35mm color film by an uncredited Al Ruban, A Woman Under the Influence is generally considered both Rowlands’ greatest performance and Cassavetes’ most popular and well-regarded work. Finding studio-based funding the film’s production was considerably difficult considering Cassavetes and Rowlands’ choice to revolve the film around a middle-aged, mentally ill housewife. The pair ended up finding their solution in mortgaging their LA home and borrowing money from friends. Though it wasn’t described by John as his most challenging movie to make, this seems to retrospectively have been the greatest practical risk of their joint career. The partners’ close friend and Rowlands’ onscreen husband Peter Falk ultimately invested $500,000 into the project himself. Luckily for Cassavetes and his students at AFI, his crew ended up mostly consisting of the school’s attendees.

The film depicts an erratic mother in a publicly harsh, at times physically abusive relationship. Instead of disregarding the mentally ill woman’s skewed sense of reality, the film humanizes her deeply to the point where by the end of the film, one is left feeling as if everybody in the world around her has made her this way, having failed her. Even so, the love between her and her husband, while chalk-full of red flags, feels powerfully vulnerable and injected with a simultaneously toxic and sensitive version of love. No one’s morals or sense of character is given the material that would enable a categorization of a person as good, bad, or too mentally ill to care for their children.

Like many of his future features, Woman ended up having no luck finding willing distributors despite enjoying moderate success in LA and New York arthouse theaters (Cassavetes would end up spending the majority of his final years calling theaters personally, one by one, with the hopes of securing screening privileges for his respective catalog of films). This complete lack of professional distribution marks Rowlands’ most infamous work as the first truly self-distributed American film. The film was mostly critically acclaimed, even securing an Oscar nomination for both John and Gena.

A Woman Under the Influence was the first example in which John’s unique directorial and inexpensive aesthetic style were publicly cheered. Unfortunately, it would also be the last. Its rejection of the classic Hollywood standard for performative realism onscreen singlehandedly flipped what audiences could come to expect from cinema onto its side. John, Gena, and their gang of recurring friends had the ability to establish an unshakeable reality that could turn absurdist at the drop of a hat. Their approach to filmmaking was framed as if cameras are left rolling on a character’s space, where moments of tension are later found in playback and cut together to make a film unbound in form.

My memory of having rented it from the local library in freshman year of high school remains deeply ingrained as a formative moment in my exposure to arthouse cinema. I remember being utterly overwhelmed and feeling certain it was the first time I had seen anything of the kind. They invented a genre: a sort of mockumentary yet dramatically-based, emotionally exposing type-film that could be both funny and terrifying at the exact same moment. I owe so much of my approach to creating stories to the filmography of John and Gena, but especially this film.

Pauline Kael’s infamously disapproving perception of Cassavetes’ directorial style is still present in his and Gena’s most publicly appreciated work. Despite leaving a mostly positive review, she can’t seem to let the experience slip by without getting a nasty word in about John and his efforts. The only attention given to his directing reads, “the scenes are often unshaped, and so rudderless that the meanings don't emerge,” this shapelessness being exactly the point of John’s attempt at destroying the formal conventions of film form as a narrative medium².

While John himself would have argued that this expected outcome of a meaning within a film is exactly what he’s against spoon feeding to an audience, it’s no secret Kael’s respected words had a harsh impact on Cassavetes’ view of critics and the art world. His rebellious nature naturally influenced him into doing more of what critics seemed to not like, as made evident with the progression of his style radicalizing in the films that came after Woman. It’s also important to note that Kael and Cassavetes’ public relationship consisted of him repeatedly pulling vengeful pranks on her, hoping to embarrass the critic as a form of retaliation for “dumbing down” his artistic intentions. Nonetheless, her success as a household name and his lack of financial stability throughout the rest of his career frames an unfortunate and probably more dramatic dynamic between the two, despite Kael’s admiration for Rowlands as a performer.

Of their truly independent works, Opening Night (1977) is the least like the pair’s other collaborations. Its narrative structure shows John playing around with supernatural elements and placing alcoholism at the forefront of Myrtle Gordon’s (played by Rowlands) relationship with every surrounding character. Interestingly enough, Cassavetes’ own struggle with alcoholism is well documented in Ray Carney’s biography on the filmmaker, allowing one to interpret this part of Rowlands’ character as a reflection of Cassavetes’ own struggle with alcohol as a creative supplement, which eventually led to his ultimate death at the age of 59. Even more interesting, Cassavetes’ character, a fellow actor and long-time fling on Gordon’s tentpole play, has a moment disapproving her excessive drinking between performances.

The feature follows Rowlands as a disturbed, middle-aged actor in the midst of performing previews before the play’s Broadway debut when an obsessive fan is struck by a car and killed just moments after signing the young fan an autograph. As rehearsals progress, Myrtle deviates more and more from the play’s script out of sheer impulse, sparking an eventual nervous breakdown while premiering the show on Broadway in the film’s grueling climax. In the feature’s infamous final act, John’s character catches onto Gena’s incessant abandonment of the production’s script and spontaneously joins her in improvising the play’s closing scene. They eventually abandon stage-rules and play off the roaring audience’s response to drive the play’s finale to a close. It’s one of the many moments of pure genius in a Cassavetes climax made even more wholesome by the duo’s uninterrupted moment of play. Their real-life chemistry is simply untamable, even in fiction.

Upon release, the film was viewed by nearly empty screening houses in less than a handful of theaters in New York and only one screen in Los Angeles. Additionally, Opening Night received nearly zero attention in New York magazines despite screening at Cannes and Berlin. It is known for being John and Gena’s least successful collaboration, having not received commercial distribution until 1991, nearly two years after Cassavetes’ death.

Cassavetes’ disapproval of the state of Hollywood lasted from the fifties up until his all too early demise in the late eighties. His infamously harsh language confronted studio systems with a simple solution: allow filmmakers to express themselves individually with final cut, or bust. In a Film Culture article aptly titled “What’s Wrong with Hollywood,” Cassavetes exclaims, “The answer cannot be left in the hands of the money men, for their desire to accumulate material success is probably the reason they entered into filmmaking in the first place” (Cassavetes par. 9). He spends the rest of the essay establishing his belief that cinema simply “cannot survive without individual expression” (Cassavetes par. 2). Cassavetes’ signature approach to cinema through the personal subject matter of his narratives, as well as his outlandish methods on set with actors and crew all simultaneously deviated from producing cliché results in his independent features.

His improvisatory “leave the camera rolling” technique captured the unconstrained energy between spirited performers and the cameramen trying to keep up with them that came off entirely differently in the overwhelmingly masculine Husbands than it does in the more tender but equally aggressive Minnie and Moskowitz. This approach was taken to its absolute maximum point with 1976’s The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (spoiler alert, a film that also made no money and was seen by practically no one upon release). The film’s demanding night shoots spotted a never-sober Cassavetes between takes, oftentimes pulling consecutive all-nighters to have time for rewriting scenes on the spot before the next day’s shoot.

With his final studio picture Gloria (1980), it became clear that John’s radical style put him at the forefront of experiencing every constraint he’d previously detailed and criticized in his Film Culture piece: his foretold prophecy was self-written. John’s “individual expression” was not only based in what he wanted to say about modern life, but in how every technical element of the filmmaking process was altered to suit his humanistic perspective. Though Gloria’s success would help John finance his next film, he would go on to share his distaste for the film in Carney’s prolific biography Cassavetes on Cassavetes. He explains, “I was bored [with the film] because I knew the answer to that picture the minute we began. And that’s why I could never be wildly enthusiastic about the picture— because it’s so simple”³. It’s this soap-opera simplicity found in his studio pictures that’s completely absent in his final and most absurd collaboration with Rowlands, Love Streams (1984).

In his penultimate film, John and Gena play on-screen siblings (out of sheer necessity) reuniting as each of the siblings’ respective partners have abandoned them. Originally produced as a stage play directed by Cassavetes and starring Jon Voight and Rowlands, the film adaptation stripped of Voight after he insisted he should direct Cassavetes’ screenplay. Despite his “from the hip” visual style being one of my favorite trademarks of his works, Love Streams (1984) is the only film of his independent works that doesn’t contain handheld cinematography, possibly in a last ditch effort to appeal to studio distributors. However, his love for telephoto lenses and shooting at home with his family and friends and turning a normally dictatorial film set into a collaborative hangout is ever-present, if not at its most potent level in Gena and John’s final feature.

In the masterpiece’s most arresting scene, Cassavetes insists Rowlands not leave his home in the rain. While the third act’s heavy storm continues raging outside, John grips onto Gena’s shoulders. “I don’t want you to go. I love you… You’re the only one I love.”

It would be the couple’s final moment together on film.

In the final years of Cassavetes’ life, he would be diagnosed with incurable hepatic cirrhosis, a product of his long term alcoholism. Though he would eventually succumb to his illness in 1989, longtime friend Peter Falk would convince him to assistant direct on the over-schedule and ultimately forgotten Columbia comedy Big Trouble (1986). Though the film bears zero resemblance or bearing to John’s style, it would be on postproduction of the picture that film journalist Joe Leydon scored one of the mogul’s final interviews. When Leydon questions the relevance of establishing life as “short and fragile” in Cassavetes’ work, John replies, “You mean, how do I look at the death sentence that’s been given all of us?. . . Everything passionate. . . has to do with someone saying, ‘Hey, this is the last time’”⁴. The inspiring interview reveals the special something of John’s attitude that invokes a rather powerful feeling within me, found both in his public dialogue and films. He announces “This is it, right now, this day that we’re living is the [last] time,” in the midst of a nearly four-year battle with his illness.

The circumstances behind John eventually succumbing to his liver cirrhosis makes retrospectively watching his films all the more inspiring: Here’s someone who said what he wanted to say, what others told him not to, persevered while doing so, and whose legacy has surpassed any ounce of recognition he received in his lifetime.

In his interview with Leydon, it feels like John’s own life is riding on the line of his words at that moment. Through his words and actions, it’s clear that what he wanted more than anything was to make films how he wanted to and for people to really SEE them. When you combine this with the infamously loving personal and working relationship between him and his wife, it’s difficult not to feel inclined to model your prospects and goals as such, or at least hope you can find something as special. Gena wasn’t just his muse or other half, her and John were two distinct individuals with nearly identical approaches to art who understood the importance of the present moment and how to express the love they shared through the tangibility of cinema.

What the Cassavetes-Rowlands dynamic ached for from a career or financially logistical standpoint never came to fruition, yet looking back over thirty years since John’s passing, the genuine widespread reverence for their projects has only grown exponentially. Maybe Cassavetes isn’t the artist to look up to for young filmmakers who dream to make their mark on the medium while attaining financial stability, but what came out of Cassavetes’ story ultimately held power in the long run as a tale of perseverance for authenticity on the silver screen and in all modes of art. If John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands proved anything in their brief time together, it’s that love transcends.

Works Cited

- Kael, Pauline. “The Current Cinema: Megalomaniacs,” The New Yorker, Jan. 2nd 1971, p.48-51.

- Kael, Pauline. “The Current Cinema: Dames,” The New Yorker. Dec 9th 1974, p.171-177

- Carney, Ray and Cassavetes, John. “Cassavetes on Cassavetes,” Farrer, Straus, and Giroux.

- Cassavetes, John. “What’s Wrong with Hollywood,” Film Culture n. 19, Spring 1959